|

| Yuri leading a workshop in 2010. http://www.peaceboat.org/english/voyg/69/lob/100706/index.html |

College and the Social Movement in Japan:

During the time that Yuri was in high school and college the labor movement, women’s movement and other social movements were active in Japan.

“When I was in there were so many social movements and uprisings. I went to Waseda University, and at that time Waseda was one of the centers of the active student movements, so we didn't have many classes going on at the time. There were always demonstrations happening. But I wasn't that interested in the student movement per se in Japan because there was so much infighting between different sects of the movement.”

“I was not that spiritual when I was a student. I was much more interested in social change. I was very interested in the feminist movement, and that's part of the reason why I wasn't interested in the student movement on campus, because it was very much dominated by men who loved to argue about all these so-called difficult theories of social change. I had more of a feminist perspective which came out from my own life experience.”

Yuri decided to leave school and join the farmer's struggle that was taking place at what is now Narita International Airport.

“It was called the Sunlika struggle. At that time the area, which is now Narita airport, was all farmland. The proposal for construction of a new international airport would change the entire into an industrial complex. The farmers were opposed to that. It became a central struggle of the social movement at that time in Japan. A lot of international media and people in the movements came to Sunlika. I went to Sunlika and stayed there with the farmers for about a half year. And there were other students like me. I met so many people involved in social change movements.”

Leaving Japan:

When she was 26, Yuri decided to leave Japan. She had been working as a journalist, a good job that she liked, writing and interviewing people, and getting published. But she felt there was something superficial in what she was doing.

“I wanted more guts in my heart. I was seeking a spiritual experience. I decided to leave Japan but I didn't know where to go. So I told myself, OK, there are two criteria to choose the country where I'm going. One is that it be very far away so I won’t come back easily. And two, a place where the language is not English. I wanted to go to a place where I didn’t know the language. So that's how I thought maybe Mexico would be good. I didn't know any Spanish. At that time, there was no direct flight to Mexico. It took two days to get there. That was in 1976.”

|

| Yuri in Guatemala in her mid-20s |

Connecting to Native Struggles:

After living in Mexico, Guatemala and Central America, Yuri eventually came to the United States in the late 1970s and sought to meet Native peoples in the United States. She lived with and traveled with people in the American Indian Movement (AIM) and learned about Native spirituality and their struggle. She also came into contact with the Nipponzan Myohoji, Buddhist peace makers, and the Japanese Buddhist nun, Jun-san, who was closely connected with AIM.

“There were already a lot of European-Americans who had contact with AIM people at that time. There wasn’t really anything special about me being Japanese. Also I looked Mexican at that time. My skin was dark and I spoke Spanish better than English then. I didn’t know English much. So I don’t think they really looked at me as a 'Japanese' Japanese. Through Jun-san and the other Japanese monks, they had so much respect for this Buddhist order and their spiritual practices and Japanese people.”

Native American spirituality and its connection to nature resonated deeply with her own spirituality as a feminist.

“Native American spirituality and practices I experienced like sweat lodges, sacred walks, or being solitary in nature really nurtured my belief in the power of nature. Since then, I have been a part of Native People's struggles and activities. Their political or social activism is based on their spiritual belief system and that really is the teaching that they gave me.”

|

| AIM leader, Bill Wahpepah, performs a ceremony. |

|

| Native leader, Bill Wahpepah, Yuri’s friend, pictured with AIM symbol in the background. |

Coordinating the World Peace March:

In 1981, the Nipponzan Myohoji Buddhist sect was organizing a year-long world peace march calling for an end to nuclear weapons. Yuri was living in Japan and pregnant at the time, so she considered what this would mean for her given the timing in her life.

“I thought, if the baby is born, I probably will have to stay home and take care of the baby. And writing is going to be difficult when baby is around. So I thought maybe I should go for a whole year to this peace march. And the baby will with be with me on the walk. And I thought, that's a wonderful way for the baby to grow up in first year, with so many different people and getting to sleep outside often. Being on the March and walking in nature would be much better for the baby than being in an apartment. And that would be healthy and mentally for me too. So I decided to do that.”

The World Peace March was to start in 1981 in seven different locations which would all end together in front of the United Nations in New York on June 12, 1982. Yuri’s role was to organize the route of walkers leaving from Japan, walking through the Hawai'ian islands, flying to San Diego and walking up to Seattle, then flying to the northern end of the East Coast and walking down to New York. On the route they would visit military bases and military sites.

By the time the walk started, Yuri had given birth to her oldest son, Ren (lotus in Japanese), who was three months old when the year-long walk began. On the walk, Yuri's role as coordinator was to assist and coordinate the traveling caravan of peace walkers during the walk. She went ahead to the next town and coordinated churches or peace organizations to welcome the peace walkers and find places for them to stay.

“Our first son was on that walk the whole time. He was three months old when we started so we always carried him. As a baby, he performed a special role as a symbolic messenger of peace, of why we were the march. We were doing this for the future generations. The peace marchers loved to carry the baby, especially in the winter time, because he was very warm to carry on your back or front. So he was cared for communally by people. We were always outside, always walking, and during the warm weather we slept outside and ate outside. So he was very much in nature his first six, seven, eight months. And I think that was good for him. He became the symbol of what we were doing.”

|

| Three generations: Yuri’s family on the peace march. L-R: Richard, Yuri’s husband, Yuri’s father, and baby Ren on Yuri’s shoulders. |

|

| Baby Ren being carried by one of the Native American peace walkers. |

In New York on June 12, 1982, the marchers finally arrived and joined over a million people from all over the world who gathered to call for nuclear disarmament. This was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest demonstration on earth at that time and included 1,665 civil disobedience arrests.

|

| June 12, 1982. One million people from all over the world (the world's largest demonstration) gathered in New York City to call for nuclear disarmament. http://www.icanw.org/1982 |

Yuri continued to be involved with issues of nuclear disarmament. Several times she accompanied US delegations to the Hiroshima Peace Conferences in Tokyo, and in 1983, as part of the Ecumenical Peace Institute based in Berkeley, helped to organize a multi-city three-month Fast for Life. People in Oakland, Paris, London, Toyko, Hiroshima and Canada fasted for days and weeks, appealing to their governments to stop nuclear armaments.

|

| Photo from the World Peace March after a ceremony of the Wampanoag Indian people. Yuri, baby Ren, the Nipponzan Buddhist monks and nun, and native American peace walkers are pictured. |

|

| Yuri and baby Ren as the World Peace March finally arrives at the United Nations in New York, 1982. |

Being a Mother and Making Society Better:

|

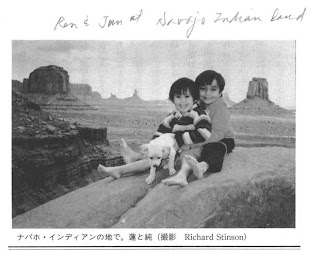

| Yuri’s two oldest children, Ren and Jun, on Navajo land. |

After the Peace March ended in New York, Yuri looked for a job that contributed to social change. She began working in child-abuse prevention, developing trainings and child abuse prevention programs. Yuri sees this work as also promoting a nonviolent society. In her words, “the violence in intimate relationships like child abuse or domestic violence have a lot in common with violence on a larger scale, like war.”

|

| Yuri loves taiko and was one of the children’s taiko teachers at the Oakland branch of the San Francisco Taiko Dojo. |

Following that, she worked for seven years as a trainer in the Office of Affirmative Action at the central administration of the University of California where she researched and developed program and curricula for teachers and staff of the university to address racism, sexual harassment, cultural diversity, disability and leadership skills needed for a diverse society.

In 1997, she returned to Japan and established the Empowerment Center, which provides training and workshops on diversity, human rights issues, child abuse and domestic violence prevention. She still continues as the director of that center today. The purpose of all her training is for participants to gain theory, knowledge and skills for effectively working in the fields of education and social services, and is rooted in an underlying principle of empowerment that “draws out an inner strength that allows you to embrace yourself." She has also been involved serving on a committee, offering consultation to lawmakers, and lobbying for changes to the law on child abuse prevention passed in 2000.

|

| Seitaka Onna (Women Walking Tall) |

|

| Yuri has written over 25 books including her autobiography, Kodomo ni Au (Meeting with the Children), published in 1994. |

Yuri has also authored 25 books for adults and children on matters of empowerment, human rights and diversity, child abuse and domestic violence.

What sustains you to do this work?

“This is a quote from Alice Miller, one of the pioneers of revealing the problem of child abuse internationally. She said, 'Fear and anxiety are contagious. But so also is a tiny bit of courage.'”

Links:

- The Empowerment Center was established by Yuri Morita in 1997 in Nishinomiya, Japan.

- Seitaka Onna (Women Walking Tall)

- Profile of Yuri Morita at the Empowerment Center

Some online articles about Yuri:

- Empowerment training draws interest across Japan in The Japan Times Online.

- "Keeping Women and Children Safe – Morita Yuri" on Peace Boat.